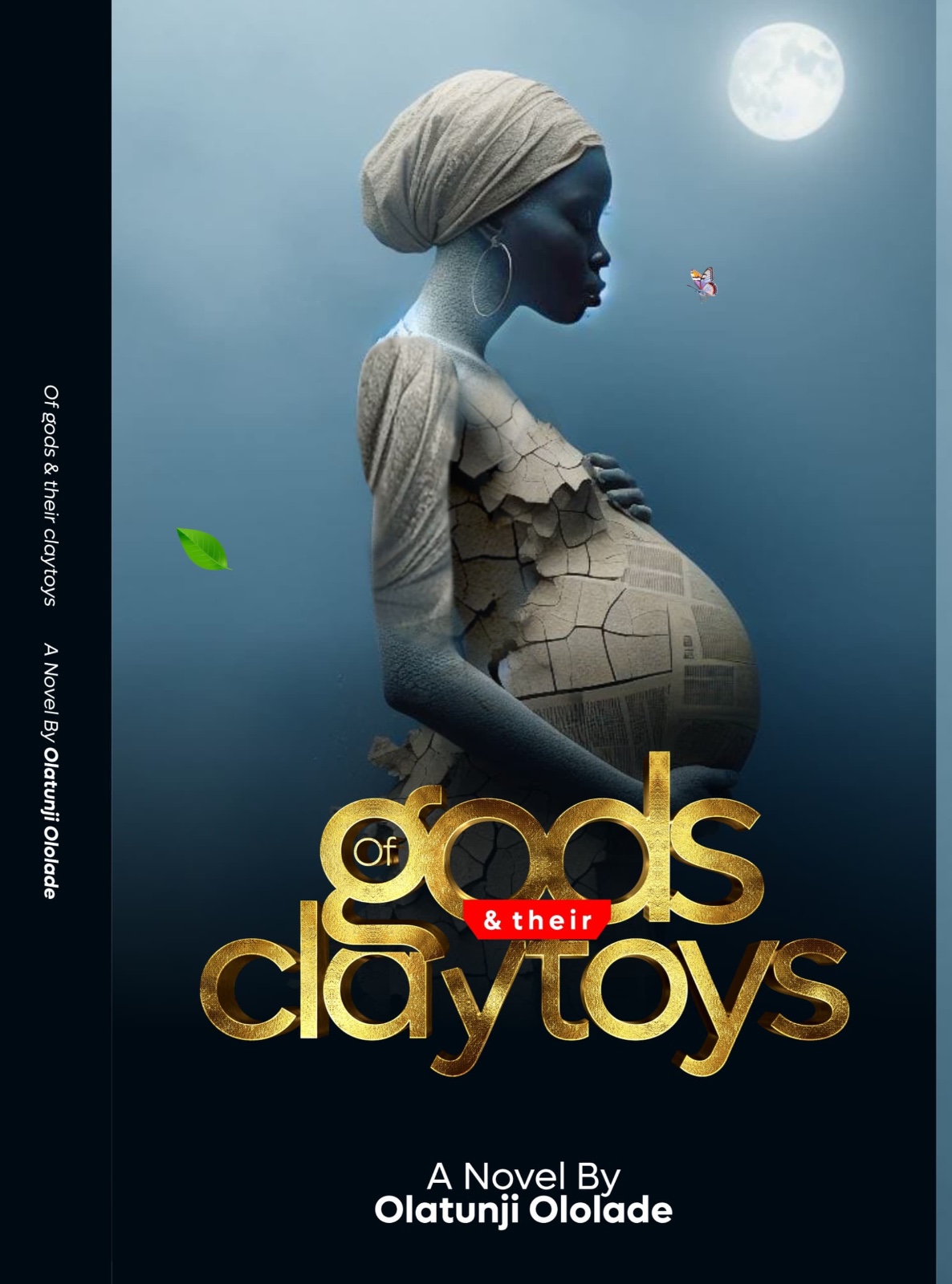

Of gods And Their Claytoys: Olatunji Ololade’s Haunting Exploration Of Fate, Identity, And The Unseen Forces That Shape Us

By Adetoun Olaitan

Labour is the crowning test of misery for the unnamed girl at the beginning of Olatunji Ololade’s Of gods and their claytoys. For the teenager, birth pangs arrive as a banishment and a reckoning. She moves through the night, distressed, her mind retreating into the imagined embrace of a home that no longer exists.

“Labour pangs swirled buoyant imagery of the parents she hardly knew in her head; lucid portraits of her mother’s splendid beauty, her father’s gracious strength and their cosy homestead amid the hills. But that was merely a retreat…At that point she would have parted her thighs to a butcher’s jackknife as long as it rid her of her burden.”

Here, Ololade sets the stage for a novel that hardly romanticises suffering but instead lays it bare. The pregnant teen is carved open by fate and expelled into a world that neither wants her nor the child she carries.

“The girl cried, the weight of impending dawn crushing upon her as the impatient bulk pried her thighs apart. She cursed as agony tore through her feeble frame, squeezing her, draining her. She screamed and thrashed about the hut, crying a river of pain into the dark. Finally, it was over. Akanke cut the child’s umbilical cord with a shard of broken glass.”

With this visceral portrait, Ololade startles the reader with the agony of a teen mother and the relentless hand of fate branding its mark upon a newborn child. This is no ordinary birth; it is a genesis bound in rejection and myth, heralded by the screams of a girl-child wronged, and the manic indifference of a society unmoored from reason.

A child is wrenched into a world that does not want him, his umbilical cord severed with the crude, jagged edge of a broken bottle. This image persists throughout the novel, speaking to the rough and improvised predestination of the child-turned-protagonist, Remilekun Balogun.

Ololade establishes quite early that he does not seek to merely tell a story but craft a reckoning – an origin story of rupture, societal stigma and myth. And it is from this primal conflict that the novel unfurls, brimming with poetic fatalism, where characters circle their destinies like moths drawn to the slow-burning edge of inevitability. Remilekun, for instance, seems yoked to a destiny he attempts to escape yet inevitably circles back to in a narrative thick with karma and woven against the backdrop of society’s crumbling conscience.

Ololade, in a masterful interplay between first-person and third-person narration, constructs a tale that is at once deeply intimate and politically expansive. At its centre is the protagonist, Remilekun, a man born in shame and rejection, a journalist whose pen becomes a sword and a curse. His narrative is one of survival, a searing awakening. Raised by a mother whose love was steadfast but fraught with ghosts of her own buried past, Remilekun grows with an abiding inhibition about his roots.

Recalling childhood with her, he says, “My earliest memory is my mother’s scent. She had a woody, smoky smell with an undercurrent of sweat which was accented by the worn Dutch wax wrappers that she tied around her thin, sinewy body… My mother and I were poor. We only had each other to depend on. And, despite these two facts, I knew that she would never let me suffer.”

The tenderness of this memory contrasts with the brutality that later unfolds, where Remilekun learns that survival may dawn in his betrayal of the woman who shed blood and sweat to raise him. Of course, Remilekun is not a hero in the classical sense. He is not sculpted from unyielding moral purity, nor is he shielded by divine providence. He is, instead, a man worn thin by conflict, by the weight of an origin he does not fully understand and by a profession that demands both cowardice and courage in equal measure. He rises from the debris of his childhood to become an investigative journalist who dares to expose the rot gnawing at the heart of his country.

When a fellow journalist, Charles Ihezua, suffers a gruesome death in an incident smeared with lies, Remilekun takes a stand, refusing to let falsehoods rewrite the truth. But it is when he uncovers and leaks damning evidence of a murder—committed by Ndoli-Edet, the political godfather of Nigeria’s President, Tamuno Wisdom—that he truly splays his life upon the altar of consequence.

For a man forged in hardship, Remilekun isn’t immune to its fissures. Caught between the trials that shaped him and the forces that seek to undo him, his masculinity unfurls as a battlefield, haunted by the men who seek to destroy him and the women who leave indelible marks upon his soul. His mother’s absence manifests as the first wound, a lesion that festers beneath his relationships.

Sophia, his lawyer and perhaps his most enigmatic confidante, is both shield and storm, ushering him toward his greatest battles while complicating his moral compass. Odu, his childhood crush, marks the first stirrings of desire, while Enitan, his benefactor’s wife, disrupts his carefully curated path with the weight of unspoken emotions. But it is Chiamaka, the feminist-writer, who perhaps most pointedly illustrates his struggle with women, expectations, and the slow erosion of self.

“But by March, the cracks had started to show. What was banter was becoming caustic. Odd remarks and insults were making their way into daily conversations, turning something he had looked forward to into something he was coming to dread. Part of the problem was that Chiamaka was an insatiable person. Her appetite for all things was huge. She ate like a newly released convict, drank like a sailor and mated like a nymphomaniac… All things he wasn’t interested in. So she got angry. And the more let down she felt, the more she lashed out. As all this was happening, Remi was orchestrating the biggest scoop of his career.”

Here, Ololade does not settle for easy tropes. Rather, he dissects the war of needs and the clash of expectations between man and woman—Chiamaka is not villainised, nor is Remilekun sanctified. Instead, they coexist in the tangled gray space, where love morphs into control and desire collides with resentment.

At its core, Of gods and their claytoys is an indictment of power—both its allure and its corruption. Remilekun’s truth-telling places him in direct opposition to the machinery of the state, but it also forces him to confront the question: Is truth enough in a world where silence is rewarded and complicity is the currency of survival? Beyond politics, the novel is also a meditation on masculinity in crisis. Remilekun’s struggles are not merely external; they are deeply personal, rooted in a world that constantly seeks to strip men of their autonomy under the guise of love, duty, and tradition.

Ololade, himself a veteran journalist, does not romanticise the press. Journalism, in this novel, is both weapon and wound—an industry burdened with bribery, cowardice, and ambition, where integrity is as easily bought as it is buried. The novel does not sermonise, but it cuts close, exposing with surgical precision the compromises that turn watchdogs into lapdogs. Remilekun’s ethical scruples ignite the fireworks that threaten to consume him. Intrigues bordering on his controversial stories quicken Nigeria’s implosion with unimaginable consequences. Remilekun eventually experiences likely resolution of questions about his roots where he least expects it.

Beneath the political intrigue and journalistic peril lies a deeper existential question: Are we merely clay toys in the hands of unseen gods, or do we shape our own destinies? Remilekun’s life is a constant oscillation between these two poles, offering no easy answers, only the savage interplay of fate and will.

Ololade’s prose is a thing of wonder—lyrical yet sharp-edged, poetic yet relentless. His mastery of alternating perspectives between first-person and third-person narration creates a story that is at once deeply personal and expansively political. The novel’s dialogues are crisp, its pacing deliberate, its emotional weight unyielding. Passion and intimacy are treated with a restraint that is rare in contemporary fiction—never descending into depravity, never exploiting the sex sells theory for profit. Ololade understands that literature, at its highest form, must be both didactic and elevated, a work that challenges as much as it indulges. He writes with the knowledge that young minds might one day read his words, and he does not squander that responsibility.

There are moments where the author’s voice tilts toward commentary, where the omniscient narrator whispers too close to the reader’s ear. But these moments are sparse, buried within the lines, and ultimately forgivable in light of the sheer intellectual and emotional force of the work.

Some books whine, and some books incise. Of gods and their claytoys is the latter—a threshing blade of a book that refuses to dull its edges to make its truths more palatable. Slipping between the first-person intimacy of confession and the connotative third-person sweep of myth, Ololade crafts an indictment and an elegy – a 326-page narrative of ruin and resistance, of love and loss, of a nation that self-destructs, and a man forging his place in a world that seeks to erase him.

Of gods and their claytoys is barely comforting; it is rather incantatory, shot through with a peculiar beauty that is all the more devastating for its refusal to console. It is a book not to be read lightly, nor to be easily forgotten.